Introduction

A Liquid Foundation: What Brodo di Verdura Is, and Why It Matters

In Italian cooking, brodo di verdura — vegetable broth — is not just a background flavor. It is the infrastructure of the cuisine. It’s what gives depth to soups, risottos, stews (spezzatini), and even sauces. It replaces water in cooking not only to add flavor, but to carry a deeper sense of homemade. A good brodo gives body to a dish, depth to its flavors, and texture to its final form. Though often invisible, its presence — or absence — is unmistakable.

Despite its essential role, brodo is often treated as a generic component, its formulation varying wildly across recipes and traditions. This project takes a different approach: to analyze vegetable broth as a system, to break it down into its parts, understand its mechanics, and reframe it not as a fixed recipe but as a dynamic space of possibilities.

This post outlines a series of broth experiments designed to explore those questions. The aim isn’t to define one perfect recipe, but to map out a space of possibilities — and offer you the tools to navigate that space intentionally.

What Is Brodo, Chemically?

Brodo is an infusion: solid ingredients (vegetables, aromatics, fats, aged cheese) are steeped in hot water for an extended time, allowing flavor compounds, nutrients, and aromatics to migrate into the liquid. Several chemical processes are involved:

- Solubilization: Water extracts sugars, amino acids, minerals, and aromatic molecules from plant tissues.

- Maillard Reaction (pre-roasted ingredients): If vegetables or cheese rinds are toasted or roasted beforehand, complex, savory flavor molecules are formed, enriching the broth.

- Fat emulsification: The presence of fat (from cheese rinds, oil, or vegetables like celery) can help emulsify flavors, giving the broth a rounder mouthfeel.

- Volatile compound retention: Temperature and cooking time affect how many aromatic volatiles remain in the broth — the same molecules that make a broth smell “rich” or “fresh.”

- Surface area: Smaller, chopped vegetables release compounds faster than whole ones, meaning cut size impacts extraction speed and saturation.

We explain all this not to complicate a basic dish, but to remind ourselves: a broth is not just “water with things in it.” It is a complex, variable process — and one worth treating with attention.

Experimental Design: Controlled Simplicity

For this experimental analysis, we limited variables to focus on a core profile. Brodo can be made with dozens of different vegetables — tomatoes, zucchini, leeks, even cabbage — but we deliberately narrowed the scope to control complexity and isolate outcomes.

We used a core trio of ingredients — carrots, celery, and onions — for a reason:

- Carrots bring sweetness and earthy body.

- Celery adds aromatic freshness and slight bitterness.

- Onions contribute umami depth and a sulfurous backbone.

To this base, we added Parmigiano Reggiano rinds, a typical Italian addition that contributes umami, salinity, and richness. It’s a shortcut to depth — and a uniquely Italian flavor profile that feels essential.

We excluded tomatoes and other variable-heavy ingredients because they alter too many factors at once: they add acidity, cloud the broth (making it torbido, or cloudy), and introduce additional umami and sweetness that’s harder to quantify. Some vegetables also introduce bitterness (like cabbage or kale) or earthiness (like mushrooms or turnips), and are harder to control across different batches.

This study focuses on a minimal yet representative version of brodo — one that is foundational, flexible, and analyzable.

Review of Existing Recipes: A Messy Tradition

Before designing our experiments, we conducted a quantitative review of brodo recipes from Italian cookbooks, websites, and regional culinary sources. The aim was to understand how much variability exists in one of the most “basic” preparations in Italian cuisine.

We analyzed solid-to-liquid ratios (grams of solids per milliliter of water) across dozens of recipes. The results were striking in their variability:

- Median Ratio: ~3.33 ml water per gram of solids

- Mean Ratio: 3.85 ml/g

- Range: 1.33 to 8.33 ml/g

This means that one “standard” brodo may be six times more diluted than another — without any clear explanation.

Boxplot (Figure 1) shows wide distribution and outliers.

Histogram (Figure 2) reveals most recipes cluster around 3–4 ml/g but with a long tail toward dilution.

Scatter Plot (Figure 3) shows a moderate correlation (r ≈ 0.43) between the amount of solid and liquid used — suggesting that other variables (like evaporation, taste preference, or cultural habits) are likely involved.

These findings reveal that brodo lacks a standardized formulation. Recipes are guided more by intuition, tradition, and family practice than by experimental reproducibility. Few sources justify their ratios, and almost none explain the science of flavor extraction.

This ambiguity led us to design a structured, controlled experiment.

The Experiment

Our objective was to investigate how key factors affect the quality, volume, and flavor of brodo — not to arrive at a single “perfect” recipe, but to map the recipe space and offer guidelines for intelligent variation.

Independent Variables Tested

We focused on three factors likely to influence broth quality:

- Solid-to-Liquid Ratio (3.0 g/ml and 3.5 g/ml):

Higher ratios = more intense flavor, but also potential over-concentration. - Boiling Time (Fixed at 60 minutes):

Long enough to ensure thorough extraction, short enough to minimize mushiness or over-evaporation. - Parmigiano Rind Quantity (50% vs 100% of veg weight):

Assesses how umami and salinity scale with rind content. - Total Liquid Volume (Fixed at 2000 ml):

To control for dilution effects across batches.

By adjusting these parameters and analyzing outcomes such as evaporation, final volume, visual clarity, and taste, we aim to build a framework for understanding how broth behaves — and how to control it intentionally.

Brodo as a Space, Not a Rule

We do not claim to have found “the best” vegetable broth. That’s not the goal. Rather, we see brodo as a space of choices — each with trade-offs. Thicker or thinner. Clearer or cloudier. Sweet or sharp. Fatty or lean.

Our work here opens that space, organizes it, and offers recommendations for exploring it with intention — based on data, not guesswork.

Methods

How We Built the Brodo Experiments

To explore how different variables affect the quality and properties of brodo di verdura, we designed a controlled, systematic experiment. The goal was not to prescribe a single correct recipe but to investigate how key decisions — such as how much vegetable to use, how long to cook, and how much Parmigiano rind to include — affect the outcome.

This section details the exact experimental setup, definitions of variables, and calculations used. Our goal was reproducibility: that anyone, anywhere, could repeat these tests and compare results.

Test Matrix

| Water (ml) | Carrots (g) | Celery (g) | Onion (g) | Parmigiano (g) | Total Solids (g) | Solid to Liquid Ratio |

| 3000 | 410 | 410 | 410 | 420 | 1650 | 1.818181818 |

| 2000 | 170 | 170 | 170 | 35 | 545 | 3.669724771 |

| 2000 | 177 | 177 | 177 | 83 | 614 | 3.25732899 |

| 2000 | 163 | 163 | 163 | 81 | 570 | 3.50877193 |

| 2000 | 163 | 163 | 163 | 81 | 570 | 3.50877193 |

| 2000 | 152.3809524 | 152.3809524 | 152.3809524 | 114.2857143 | 571.4285714 | 3.5 |

| 2000 | 126.984127 | 126.984127 | 126.984127 | 63.49206349 | 444.4444444 | 4.5 |

| 2000 | 103.8961039 | 103.8961039 | 103.8961039 | 51.94805195 | 363.6363636 | 5.5 |

| 2000 | 67.22689076 | 67.22689076 | 67.22689076 | 33.61344538 | 235.2941176 | 8.5 |

| 2000 | 57.14285714 | 57.14285714 | 57.14285714 | 28.57142857 | 200 | 10 |

| 2000 | 285.7142857 | 285.7142857 | 285.7142857 | 142.8571429 | 1000 | 2 |

| 2000 | 285.7142857 | 285.7142857 | 285.7142857 | 142.8571429 | 1000 | 2 |

| 2000 | 285.7142857 | 285.7142857 | 285.7142857 | 142.8571429 | 1000 | 2 |

| 2000 | 285.7142857 | 285.7142857 | 285.7142857 | 142.8571429 | 1000 | 2 |

Overview of Variables

We selected three key variables to manipulate:

| Variable | Levels Tested | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Boiling Time | 30, 60, 90 minutes | Chosen to represent short, standard, and extended simmering. |

| Solid-to-Liquid Ratio | 1.8 ml/g and 10 ml/g | Based on observed ranges in recipe analysis. |

| Parmigiano Quantity | 0.5× and 1× total vegetable weight | Typical Italian brodo additions vary; these levels test umami intensity. |

All broths were prepared in 2-liter batches (2000 ml starting water volume), and all vegetables were chopped into roughly 2–3 cm pieces to standardize surface area exposure.

Note: An initial test was conducted using a 3000 ml water volume, but subsequent batches standardized to 2000 ml due to resource limitations and to reduce post-cooking volume.

Definitions and Calculations

To design a consistent and controlled experiment for Italian vegetable broth (brodo di verdura), we needed a precise way to define how much of each ingredient to use. The formulas below explain the logic used to calculate ingredient amounts while varying only specific parameters (like the water-to-solid ratio or the amount of Parmigiano).

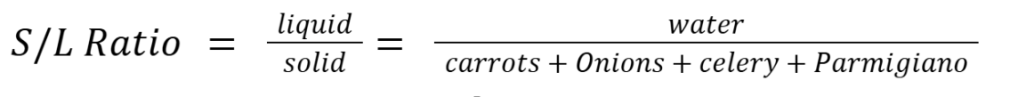

Solid-to-Liquid Ratio

This formula calculates the water-to-solid ratio (ml of water per gram of solids), a central factor in the experiment. It determines how “diluted” or “concentrated” the broth will be. A lower ratio (e.g. 3.0 ml/g) means more vegetables per unit of water — resulting in a richer, more intense broth. A higher ratio (e.g. 4.0 ml/g) makes a lighter broth.

We use this formula in reverse to calculate how much vegetable mass we need, given a fixed amount of water (2000 ml) and a target S/L ratio (e.g. 3.5 ml/g).

For simplicity and control, we decided to split the vegetable component equally among the three classic base ingredients of Italian brodo:

- Carrots

- Onions

- Celery

This avoids any one flavor dominating and helps standardize flavor extraction.

Parmigiano Rind Quantity

This formula links the amount of Parmigiano Reggiano (specifically, Parmigiano rinds) to the amount of carrots — and therefore to the total vegetable mass — by a multiplier:

- If

weight = 1.0, you add Parmigiano equal to the weight of carrots. - If

weight = 0.5, you add half as much Parmigiano as carrots (or celery, or onions).

This way, you can test how different levels of umami (from Parmigiano) affect the flavor, without changing the base broth too drastically.

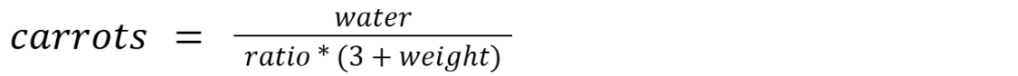

Deriving Vegetable Mass from Water and Ratio

This is the “master formula” used to calculate how many grams of each vegetable to add.

Let’s unpack it:

- Water / Ratio gives the total grams of solids you’re allowed to use, based on your selected S/L ratio.

- (3 + weight) is the number of parts in the solid mixture:

- 1 part carrots

- 1 part onions

- 1 part celery

weightpart Parmigiano

By dividing the total solid mass by (3 + weight), you get the weight of one part — which is the amount of carrots, and by extension also onions and celery. Then Parmigiano is just a multiple of that, as explained above.

Ingredients

Each batch used the same foundational vegetable base:

- Carrots (≈33%): mild sweetness and color

- Celery (≈33%): aromatic sharpness, slight bitterness

- Onions (≈33%): umami and base complexity

- Parmigiano Reggiano rinds: traditional umami enhancer

These three vegetables form the canonical base of Italian vegetable broth, known for its versatility and subtlety. Parmigiano rinds are a culturally rooted addition, known for contributing savory depth and complexity. We avoided tomatoes and other variable or acidic vegetables to reduce turbidity (torbidità) and prevent flavor profile inconsistencies.

Cooking Procedure

Each broth was prepared under identical kitchen conditions, using the following standardized procedure:

- Vegetables and cheese were weighed according to test condition.

- All ingredients were added to a large 5-liter stainless steel pot.

- Water (2000 ml) was added to the pot.

- The pot was placed on a gas burner at maximum heat until the first sign of boiling was observed (small rolling bubbles).

- At the moment boiling began, heat was reduced to the lowest setting, the timer started, and the lid was placed on the pot.

- The broth was simmered for 30, 60, or 90 minutes, based on condition.

- After the timer ended, the pot was removed from heat and allowed to cool for 10 minutes.

- The broth was filtered through a fine-mesh sieve to separate solids from liquid.

- The final volume was measured using a graduated cylinder, and evaporation loss was calculated.

Key Notes:

- Lid Use: A lid was used throughout cooking to minimize evaporation and preserve volatile flavor compounds.

- Simmering Control: While exact temperature was not digitally measured, all batches were maintained at the lowest stable simmer after initial boil.

Recorded Observations

For each batch, the following were recorded:

| Metric | Description |

|---|---|

| Initial vegetable and cheese weights | To verify W/S ratio and cheese proportions |

| Boiling time | 30 / 60 / 90 min |

| Final broth volume (ml) | Post-filtration yield |

| Evaporation (ml) | Evaporated Volume = Initial Volume – Final Volume |

| Flavor Ratings | See below |

To systematically assess the quality of each broth sample, we defined a structured flavor profile framework consisting of five sensory dimensions, each rated on a scale from 1 to 5:

- Intensity

How strong or weak the overall flavor of the broth is.- 1 = very faint or watery

- 5 = extremely concentrated, assertive flavor

- Balance

The perceived harmony among flavors — no single ingredient should overpower the others.- 1 = unbalanced or dominated by one component

- 5 = well-rounded and integrated flavor

- Body

The tactile quality of the broth — how “full” it feels in the mouth.- 1 = thin, watery mouthfeel

- 5 = rich, full, and satisfying texture

- Clarity

Both visual and taste-based clarity: Is the broth murky or clean in taste and appearance?- 1 = cloudy and muddled

- 5 = clear in both look and flavor separation

- Aroma

The strength and pleasantness of the broth’s smell, before and during tasting.- 1 = faint or neutral aroma

- 5 = vivid, fragrant, and inviting

Each broth was evaluated using these five criteria immediately after cooking and straining, to maintain consistency and freshness in tasting.

Results and Reflections

The data showed some clear patterns. First, broths with a solid-to-liquid ratio of 3.5 were consistently stronger in flavor than those with a ratio of 3.0 — higher scores in intensity, body, and aroma. The tradeoff was that they also tended to be a bit cloudier. But overall, if you want a richer, more flavorful broth, going closer to 3.5 is worth it. For me, a ratio around 2 hits the sweet spot — enough strength without being heavy — but you should try a few and see what works for your taste. Just remember, going below 1 doesn’t make sense (you’d have more solids than liquid), and going above 3.5 starts getting into bland territory unless you really want a lighter broth for something specific.

The Parmigiano levels also made a difference. Batches with 50% Parmigiano (by weight of veg) had a good amount of umami and mouthfeel without overpowering the broth. The 100% Parmigiano batches were more intense but sometimes out of balance, especially in the lighter broths. So, unless you’re going for something really cheesy, I recommend sticking with 50% Parmigiano. Cooking time also mattered. 30 minutes wasn’t enough — the broths tasted thin and underdeveloped. 60 minutes was better, but 90 minutes consistently gave the best flavor, aroma, and body. It’s worth the extra time. In terms of volume, we saw around 100–150 ml of evaporation loss, even with the lid on — so keep that in mind if you need a precise yield.

Couple of practical notes from the tests: cut your carrots smaller than the onions and celery — they’re denser and have less surface area, so cutting them in half or smaller helps flavor extract more evenly. I start the heat on high and switch to low once it boils, but if you want to experiment, you could start on low from the beginning or even add some ice (just factor that into your water weight). And don’t throw out the boiled vegetables — they’re still useful. You can blend them into soup, stir them into risotto, or freeze them for later. Personally, I love turning them into a simple veggie soup with a little of the broth.

| Variable | Sweet Spot (Recommended) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Solid/Liquid Ratio | ~2.0–3.5 | Richer = stronger, 1.0 is minimum |

| Cooking Time | 90 minutes | 60 min okay, 30 too weak |

| Parmigiano % | 50% of veg weight | 100% adds richness, but can unbalance |

| Veg Cut Size | Carrots smaller than others | Especially helpful for better extraction |

| What To Do With Veg | Soup, sauce, freeze, risotto | Don’t waste them! |

Conclusion

The goal of this project wasn’t to find the perfect vegetable broth — it was to understand how it works, what variables matter, and how to make smarter choices when cooking it. Brodo isn’t just “water with stuff in it.” It’s a system. How much veg you use, how long you cook it, whether or not you add Parmigiano — these all change the outcome. What we found is that there’s a range of good options, not one fixed answer. You don’t need to follow a strict recipe. You just need to understand the space you’re working in. Use that space to decide what kind of broth you want — stronger, lighter, clearer, richer — and adjust from there. Cooking this way gives you more control, and better results. It also makes the process more fun.

Leave a comment